Everest: il capo cordata

La traduzione in italiano dell’intervista è qui: SCRITTORI A VENEZIA. Mark Medoff

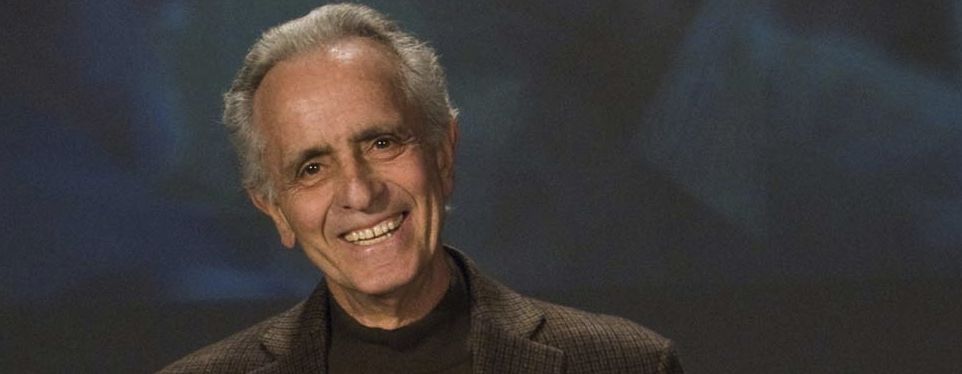

Mark, thanks so much for accepting our interview. Your career as a playwright and a screenwriter is legendary and unique. You signed ‘Children of a Lesser God’, ‘City of Joy’, ‘Clara’s Heart’, ‘When You Comin’ Back, Red Ryder?,’ just to say a few titles. Have you ever thought about the secret of your success? What’s your advice for all the young writers in the world who are trying to rise from the ranks?

I had great mentorship as a young writer. At 19, I met Professor Fred Shaw at the University of Miami. He told me the crucial measures I needed to take toward success. I have repeated his advice to my own students for almost 50 years. “Don’t do it if you don’t have to do it, because the amount of rejection you’ll face while you find out if you can do it demands you have to be totally committed or psychotic. You’ll have to write every day for at least an hour for 10 years before you can expect anyone but me or your mother to care. Writing is rewriting. You can’t wait for inspiration to strike; you write the way a marathoner trains for the Olympics. And, finally, nobody knows how to teach you to write: You teach yourself.” When I turned from prose writing to playwriting, I was surrounded by encouragement and wisdom from the people I worked with in tiny Las Cruces, NM.

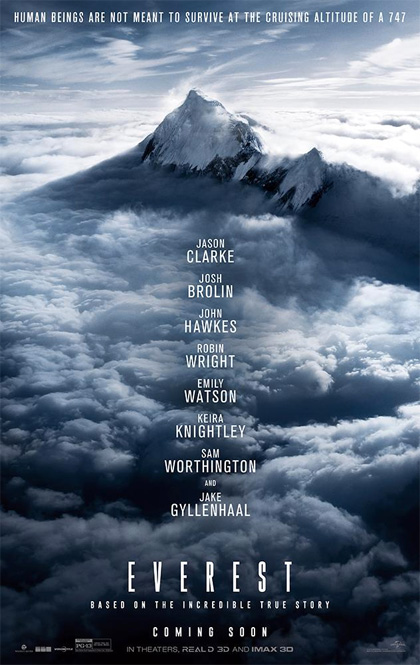

Baltasar Kormákur’s ‘Everest’ will open the 72ndVenice Film Festival. You are one of the writers who have worked on this project, but you did not get the screen credit. How could that happen?

I was the first of 6 writers. The replacing of writers in Hollywood moviemaking is like using up a roll of toilet paper. Don’t replenish the roll, replace it. I started on the project in 1997. I did 20 or so drafts over two years. As in many cases in everyone’s screenwriting career, the movie gets a green light – Go! – then the light turns red. Then green! Then red! When Working Title resurrected the movie around the turn of the century, I was no long interested. I had turned 60 and decided I didn’t want to work for hire as a screenwriter anymore. Lo and behold, the movie was shot last year, 17 years after I wrote the first drafts. Because there was an army of writers employed, the script went to credit arbitration with the Writers Guild of America. I went back through all my scripts and the shooting script with two of my brightest students. We concluded I had still initiated plot points and character nuances, still had a good deal of dialogue, and still should get credit for 60-plus percent of the shooting script. The arbitration committee concluded final screen credit should go to the last 2 writers, largely, it seems, because they had included a third character into the final mix, this third character equal in weight to the two main characters as I had defined them. In my scripts, that character was less a “star” presence because, at that time, Universal (my employer) did not own that individual’s life rights; thus I wasn’t allowed to interview him.

The Writers Guild of America is often invoked to solve this type of situations with its Arbitration Committees. In spite of the outcome, how do you judge your experience?

The person in Arbitration I dealt with at the WGA was terrific. She was always available to answer my questions. The task given to arbiters in deciding final screen credit is a formidable one. I have nothing but respect for those among my brethren in the Guild who are willing to determine, like Solomon, how to divide the baby.

Well, let’s forget about the credit, but we can’t help asking you a few questions about your work on this film. Everest is based on the bestselling book ‘Into Thin Air’, written by American writer and mountaineer Jon Krakauer, who took part in the tragic 1996 expedition. Krakauer was fiercely criticized by some other survivals. What was the main difficulty you had to face while adapting this true story to screenplay?

I didn’t have the right to Jon’s book, so I didn’t read it. I had a few life rights. For the most part, I depended on the memories of two of the survivors. From the basic facts of an article in (I think) Life Magazine, and the testimony of my two survivors, I reinvented the events on Everest. The wife of one of the team leaders was kind enough to tell me about her phone calls with her husband, she at home, he on the top of Everest, dying. Without life rights to several participants’ lives, I was restricted in how I could portray certain elements of the tragic events on Everest.

Sean Penn’s ‘Into the Wild’ was based on another Krakauer’s non-fiction book. Did you consider that film while thinking of your adaptation? More in general, how did you prepare to write about such an extreme happening?

The only guide I had in reconstructing the events was to adhere to the basic facts and to try to reinvent the real people involved in a fair way. The survivors I spoke to gave me some character traits of others, from their points of view, of course.

Every time that I think of adapting a book into a screenplay, my mind goes to Charlie Kaufman and his crazy spectacular struggle (‘Adaptation’, 2002). You worked on several adaptations during your career. How do you handle the process of adaptation? Can you reveal some of your tricks to us?

I’ve found in creating a ‘fictional’ account of real events involving real people, my allegiance tends to be to the real people, to protect them from my own appetite to exploit them for ‘dramatic purposes.’ In fact, I’ve had three experiences with movies that didn’t get made, based on real lives, because I declined to include certain inflammatory events I was uncertain happened as reported to me by other than the main subject of each script. In two of the cases, a highly placed executive at a major network and, in the third, a head of production at a major studio, suggested I include scenes involving a main character having an affair outside his/her marriage. “These are real people,” I said in both cases. “I’m not making up crap which will reflect badly on them and become part of a ravenous gossip machinery.”

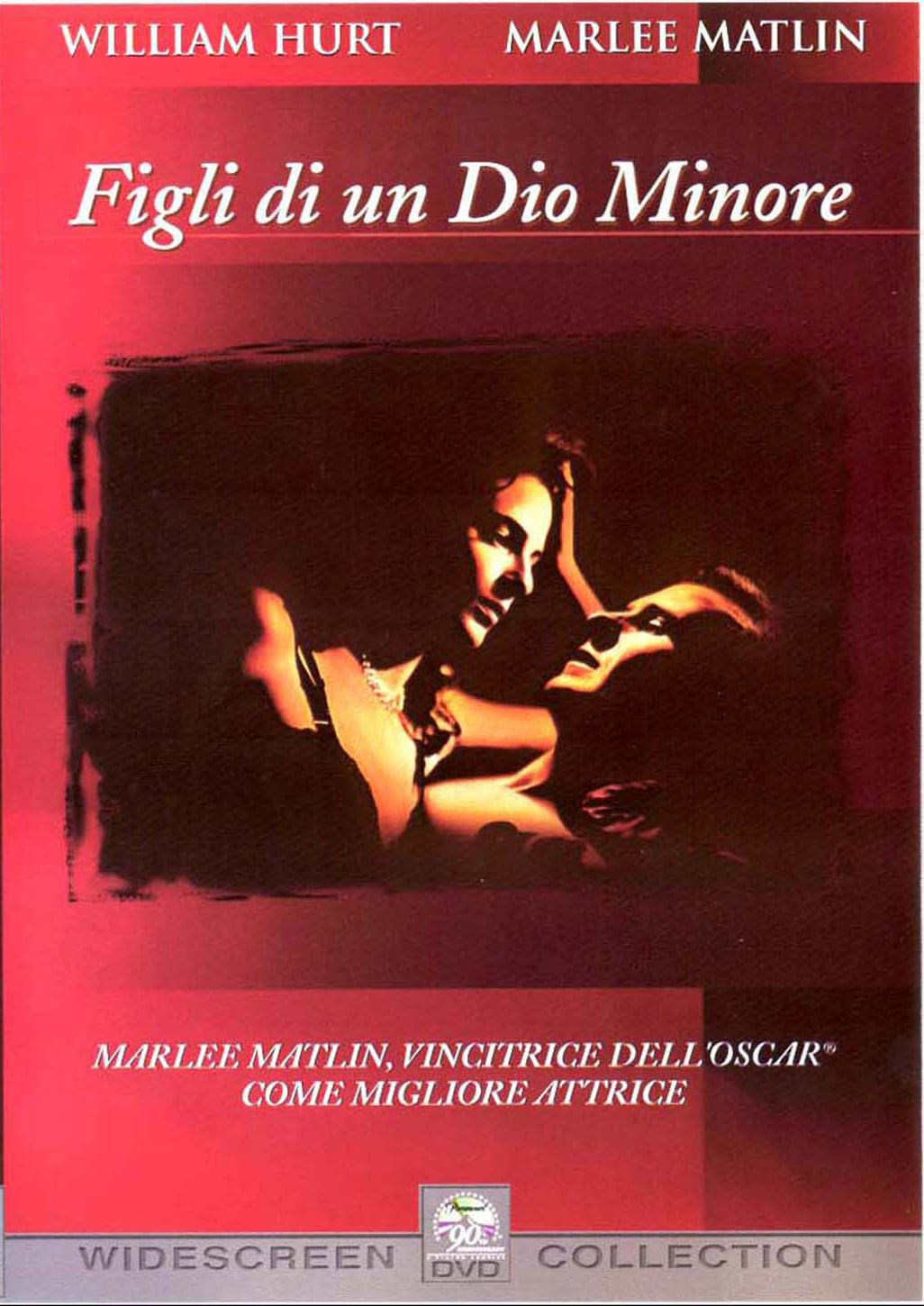

In many of your scripts, you are able to touch universal themes – like a good screenwriter is supposed to do – yet always focusing the story on the leitmotif of ‘diversity’: everything in the perspective of a very careful eye. For instance: ‘Clara’s Heart’ is pivoted on the racial theme, while ‘City of Joy’ on the poverty, and finally – in ‘Children of a Lesser God’ – the thematic of the right ‘to love anybody’ (even your Professor) is inextricably interlaced with the topic of the deafness. So, your creative process is ‘deductive’ (starting from the general and then encompassing the particular) or – on the contrary – is ‘inductive’, where you start from a narrow and realistic view to embrace a wider and transcendental one?

In the case of the movies you reference, I was adapting books. My first responsibility with a book, I feel, is to represent the author of the book worthily. Do I alter, adumbrate, abridge? Sure. I also picked things to adapt that appealed to some moral sensibility. As to work that erupts entirely out of my own head, virtually anything can get me started, though almost always – and almost immediately – there is a social-philosophical idea running around my head. But that idea is that: an idea. The idea helps me create the arenas for conflict among characters, but it’s the discovery of, the living with daily sometimes for years, the refining through readings and rehearsals of the characters who emerge to carry the burden of the idea who are most important to my creative process. Literature is about behavior. And inevitably, I am all of my characters equally, the ones I adore and the ones who terrify me. I have no fear whatever of going to the depths of the pollution inside me to create ‘real’ and dynamic characters whom excellent actors bring to life.

How much of autobiographical there is in your works? We take for granted that every writer takes inspiration both from personal and non-personal facts, but if you had to decide, would you say that you mainly take inspiration from your own life or from the direct observation of the others’ ones?

I am an inventor from observation. As I said, I will become anybody who shows up in and wants to get out of my head. Early on, discovering I had a certain ability, I wrote about the ‘great, misunderstood, angry me.’ Fortunately, I learned before my teens were gone that I was the least interesting subject as a ‘character’ available to the me who did the writing. I’m a watcher, a listener, and then a thief of time, space, and character, who tries to be balanced in representing our badly evolved species.

You just reminded me of when I met with the Italian master Tonino Guerra (‘Amarcord’, ‘Blow-Up’, ‘Casanova 70’). He told me he constantly wrote down lines heard around, and then used them in his scripts. Do you think that words caught from our daily life can help a writer make his work more real?

As noted above, I watch and listen. Though I rarely hear verbatim dialogue that I then incorporate into something in progress. At the same time, I helplessly collect abstracts of all I see, hear, invent, think.

You’ve written as successfully and happily for both movies and theater. Some of your films are based on your own plays. Pros and cons of these two languages… Which one do you feel more comfortable with?

I could easily never write or direct another movie. I have to write and direct for the theater. The theater allows me to say more and to dare more. And the power of live actors exchanging heat with a life audience cannot be matched by a flat projection surface on a wall. The greatest pleasure I have in my work once it has left my house is the rehearsal process in live theater, always three weeks or more. I am a very good re-writer; l love the collaboration of separate spirits who share the journey of a play’s fate. In movies, I’ve never been involved in a prep period where we had more than a few days of rehearsal – if that.

You have written some radio plays as well. This is very interesting since – as you know – nowadays they are very rare, even if some podcasts are sort of replacing them. Did you like it? Could you tell us the main criticalities encountered in the radio by a screenwriter – who has always been taught ‘not to tell but to show things’ in their own scripts, and that in the radio cannot follow this motto?

The couple of things I’ve done for radio were simply fun, because the challenge was to write good dialogue that could be supported by sound effects. Nothing to look at for an audience but what the writer and his/her collaborators put into the mind’s eye of the listener.

Do you think of meeting some kind of target (read: audience) while writing?

My thought about audiences is always the same: In a time of increasingly less attention span, how do I keep them awake, alert, and paying attention? Each experience is different. Though in my theater work, there is no question that I am increasingly aware as the process progresses of trying to reduce the convoluted verbiage I am prone to and adore. My wife says, “Don’t be stingy, don’t cut too much.” The trimming and tweaking process is a delicate procedure. I have little compunction, though, about remaining open to suggestions for cuts.

In 2000, you produced and directed the documentary ‘Who Fly on Angels’ Wings’, about a mobile pediatric unit traveling the underserved areas of New Mexico. A writer is used to originating, creating and guiding facts and characters, whereas who makes documentaries is supposed to do the opposite. How did it go for you?

I approached the documentary (I’m now doing two others) as I would a fictional piece. For me, everything is three acts, whether a piece is intermission-less or two acts or three acts. And every scene within a play, movie, or documentary is three acts. We enter here, something happens, we are ejected into the next scene.

Adapted from a Truman Capote’s short story, Children on Their Birthdays was your directing debut. How would you describe that experience? How did you cope with the writing of someone else?

I worked with Doug Sloan over the course of six years on his adaptation. I know how I like to be treated in a writer-director relationship and so treated Doug as I would want to be treated. Once on the set, I didn’t always have time to call him back in Los Angeles and ask him about a change I wanted to make. But, before he departed the rehearsal process, he told me he trusted me to do what was best for the movie. As a director, I was in the perfect position for me: In charge. I was directing my first movie at age 60 because I had made a deal with my wife at age 34, when I was offered my first movie to write and direct, that in order to keep our young family together and for us to stay married, I wouldn’t go off to Hollywood to direct movies. The deal was I could direct movies after the kids were all out of the house. Thus, age 60.

Do you think that a writer should always be on set during the filming?

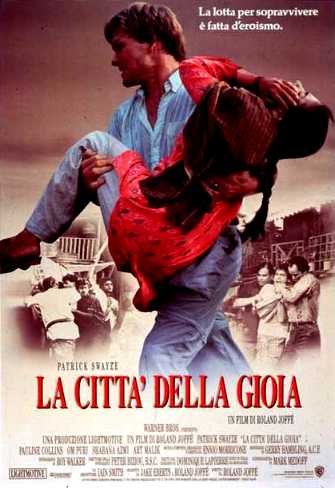

Making a movie is quite different from sculpting a play. In the theater, rehearsals are about the play; in movies, though the script is first, once the machinery of a shoot begins, I’ve found that the director doesn’t have much time to talk to me. On ‘City of Joy,’ Roland Joffé and I talked a lot by phone. On ‘Off Beat,’ I was present, though not as much as the writer as an actor. The best situation for me is to be both writer and director.

Teaching has a special place in your life. Do you believe that a good writer should be a good teacher as well?

I believe in mentorship. If I can offer something to someone, then I should do that. I happen to love classroom teaching. I still teach a course each semester at New Mexico State University. I alternate playwriting, screenwriting, and a literature course about what’s happened to the American hero (and that word includes male and female) since World War II. In addition, I go several times a year to other universities for visits in which I engage students in short but intensive experiences. One of my own mentors told me when I started teaching college: “The best teaching situation is the one in which the teacher teaches the students and the students teach the teacher.”

Let’s talk about the projects in which you involved your pupils. On ‘100 MPG’, ‘Boom’, and ‘Refuge’, you used a combination of professionals and students. Why? How was that?

I had a specific purpose in including my students in the two shorts and one feature you mention. New Mexico is a very popular place to film. However, most of the work goes to northern New Mexico (Albuquerque and Santa Fe), where the crews, the sound stages and post-production facilities are. We don’t have the facilities (yet) to compete. In the Creative Media Institute for Film and Digital Arts at New Mexico State University, we have on faculty four filmmakers who have made features in the past seven years, using a combination of professionals and students. When we hire professionals to come to us to work on a project, we make clear that the professional will be teaching as well as performing her/his specialty. We hope to impress on production companies that we’re turning out students who can work under professional leadership to fill out crews. We want to attract films to southern New Mexico so that we can keep our graduates here and employed. The state, the city, and the university are currently working together in an effort to build a state of the art sound stage and post-production facility on the NMSU campus. I have always told my children and my students this: If I tell you can do something, you can do it.

In Italy, there is a heavy separation between university and the market. The recruitment process for the writers is quite obscure and still appears to depend on personal connections (friendships, family) or political memberships. Would you tell us how it works in the United States?

If playwrights become known for their theater work, the movies come after us. An established screenwriter can make an excellent living so long as she/he understands that the system uses writers like toilet paper. ‘Everest’ is a good example. Did the producers really need six respected writers to tell that story? The contrast between theater and film writing is astounding: The theater respects the writer’s primacy; the opposite is the usual case in film. No doubt, independent filmmaking and crowd-sourcing are proliferous today, in good part, because the old system of using writers to wipe the overstuffed hind quarters of the studio beast became insufferable. I tell my students to enter competitions, to make a good short movie, get into some festivals, network with people trying to get where they’re trying to get, and follow the lead of those who have made quality movies by banding together and offering remuneration if the movie breaks out in one of the several markets available to us as non-studio moviemakers. Each year there are examples of “small” movies that break into the bigger markets. HBO, Showtime, Amazon, Netflix, AMC, iTunes, to name a few outlets, have changed the landscape for the adventuresome.

In your opinion, what is the motor that pushes people to write, and why not everybody is able to become a writer? What is yours?

There are no new stories, my mentor, Fred Shaw, told me. The genius of the individual writer is her/his ability to make the familiar fresh. I read voraciously as a kid; but, when the impulse to write took me over at age fifteen, my “style” was something that came intuitively from somewhere within me, not something I went in search of beyond my imagination. E. B. White said, “Style is the sound our words make on paper.” Simple. Our individual voices are inexplicable. Fine. Like many writers, I’m a depressive personality. Writing, I found at a young age, forestalled depression. Wait over there, I’ll be with you shortly! Early on, in college, I wrote through most of my classes. And almost flunked out of college my first year. I told myself I had to create rules for myself. Do my school work, homework, preparation, and then I can write into the night. Discipline. But I’m a wildman, a free spirit, a revolutionary. Sure, sure. But disciplined. I learned in my twenties how to operate the idea and eloquence machine that was me. I still operate the machine the same way: Do what I must in the real world, so that I can enter guilt-free into my imagination and battle the demons that would gnaw me into particulate matter.

What is the movie that you liked more writing so far? Which is the one you consider your best work – regardless of the critics’ judgment – and why?

I always love most what I’m working at on any particular day. I love the rehearsal process, the collaboration. But I know, even at the outset, nothing is going to be perfect in design or execution. The ultimate joy is the journey. Writing, then doing a play with live actors and designers, getting in front of a live audience – unbeatable. The movies I enjoyed writing the most are the ones where the director and I became ego-less parts of each other. I loved doing ‘Off Beat’ because Michael Dinner and I would make each other laugh a lot; ‘City of Joy’ because Roland Joffé and I were both vastly over-educated; we had far-ranging conversations beyond the ultimately trivial business of making movies. And, of course, I loved working with my son in law, Ross Marks, who isn’t me exactly, but with whom I am so in tune. My favorite movie I’ve written to this point is ‘Homage,’ based on my play ‘The Homage That Follows,’ adapted and produced by me, directed by Ross. It went to Sundance, it was a kind of movie I think of as ‘intellectual brutality.’ One of my favorite movies of all time, ‘Five Easy Pieces,’ I would put in the same category.

Which is your favorite scene among all the ones you’ve written? What is it about?

The opening scene of ‘When You Comin’ Back, Red Ryder?’ Two characters, Angel and Stephen, about whom I first wrote in the early 1970s. A decade later, in Kenya, Stephen started talking to me again. Subsequently, I wrote two more plays with Stephen at the center. In the third, Angel returns and meets Stephen for the first time in over a decade. The third play, ‘The Heart Outright,’ is now a movie, which I trust will be in some film festivals in 2016 (How wonderful if we could bring the movie to Italy!) The scene from ‘Red Ryder’ opens the play. Stephen is the night cook at a diner in 1969. Angel is the day cook. They come together in the early morning and carry on an elusive love affair.

If you want to read the scene, click here: RED RYDER Scene

In your very rich track record, there’s no television. Is it a choice?

Long and boring story. In the beginning (I promise not to answer with all of my own ‘Genesis’), I wrote several scripts for television that didn’t get made for reasons referenced elsewhere. My main interest was the theater. In the late 1970s when I began to accept screenwriting offers, filmwriting was more lucrative. In the early 1990s, my son in law, Ross Marks (‘Homage,’ ‘Twilight of the Golds,’ and the currently in post-production ‘The Heart Outright’) and I pitched two television series. The caveat was that I wanted to shoot in Las Cruces, New Mexico, where I live. My wife Stephanie and I had long ago agreed we weren’t moving our family to Los Angeles. At the last minute, in the case of both series, we were told, no, we wouldn’t be able to shoot outside Los Angeles. Ross and I are currently preparing to shoot the pilot of a script of mine (based on my early play ‘The Wager’), set at New Mexico State University and in Las Cruces. Because independent filmmaking has become so formidable, we feel confident we can raise the funding to make the pilot, then approach one of the myriad outlets for new material intended for television screens (and, inevitably, cellphone and computer screens).

Netflix, Amazon, Hulu & company – The future of the audiovisual recounting seems to spring from the web. What do you think about it?

I worry about the size of the viewing platform. What happens to those fabulous wide shots we work so hard on? On the other hand, I’m going to try to accommodate where the potential respondent to my work is in the evolution of viewership. I can’t roam the streets and order someone watching a great movie on a cellphone to get into a movie theater. I am reminded almost daily by a student, a friend, a colleague, that she/he saw this fabulous movie discovered by accident while browsing Netflix, Amazon, or Hulu. Would I rather someone watch my work on a cellphone or not at all? Yes.

We created the Writers Guild Italia two years ago in order to defend the Italian writers, because unfortunately our rights are constantly ignored or infringed in Italy. What do you think about the work that the guilds do?

I’m deeply grateful for the work of the guilds I belong to: actors, directors, but especially playwrights and screenwriters. In the theater, the playwright is the last word, literally and legally, by contract; in film, without the Writers Guild, I suspect we would be altogether slaves rather than high-priced prostitutes. At age 60, when I stopped offering myself for hire as a screenwriter, it was in great part because the studio system was massively alienating to me as a creator of worlds and the people who inhabited those worlds, for all of which, ultimately, others took or shared credit.

Are there any Italian films which you feel inspired your writing somehow?

In college in the late 1950-early 1960s, then in graduate school in the mid-1960s, like much of my generation – and especially as a young writer in search of myself — I fell in love with Rossellini and Fellini – wow, look what you do with reality! And then there was Antonioni, who was an extraordinary education in storytelling and the limitless possibilities for character nuance. Ultimately, though, the form which helped create me as a person and an artist was – and remains – the novel. I would rather read a novel than watch a movie or television. Myriad novelists gave birth to various incarnations of me; in college and graduate school, I was awakened daily to new possibilities by Thomas Wolfe, William Faulkner, Emily Bronte, Bernard Malamud…’And so it goes,’ as Mr. Vonnegut said.

It was fantastic for us to be able to chat with you. I guess you’re not going to Venice this year, but we hope to see you again in Italy very soon.

Thank you very much, Mark! Grazie mille!