Montanha

Hi Joao, fist I ask you a fast pitch of the film, can you tell me what is about?

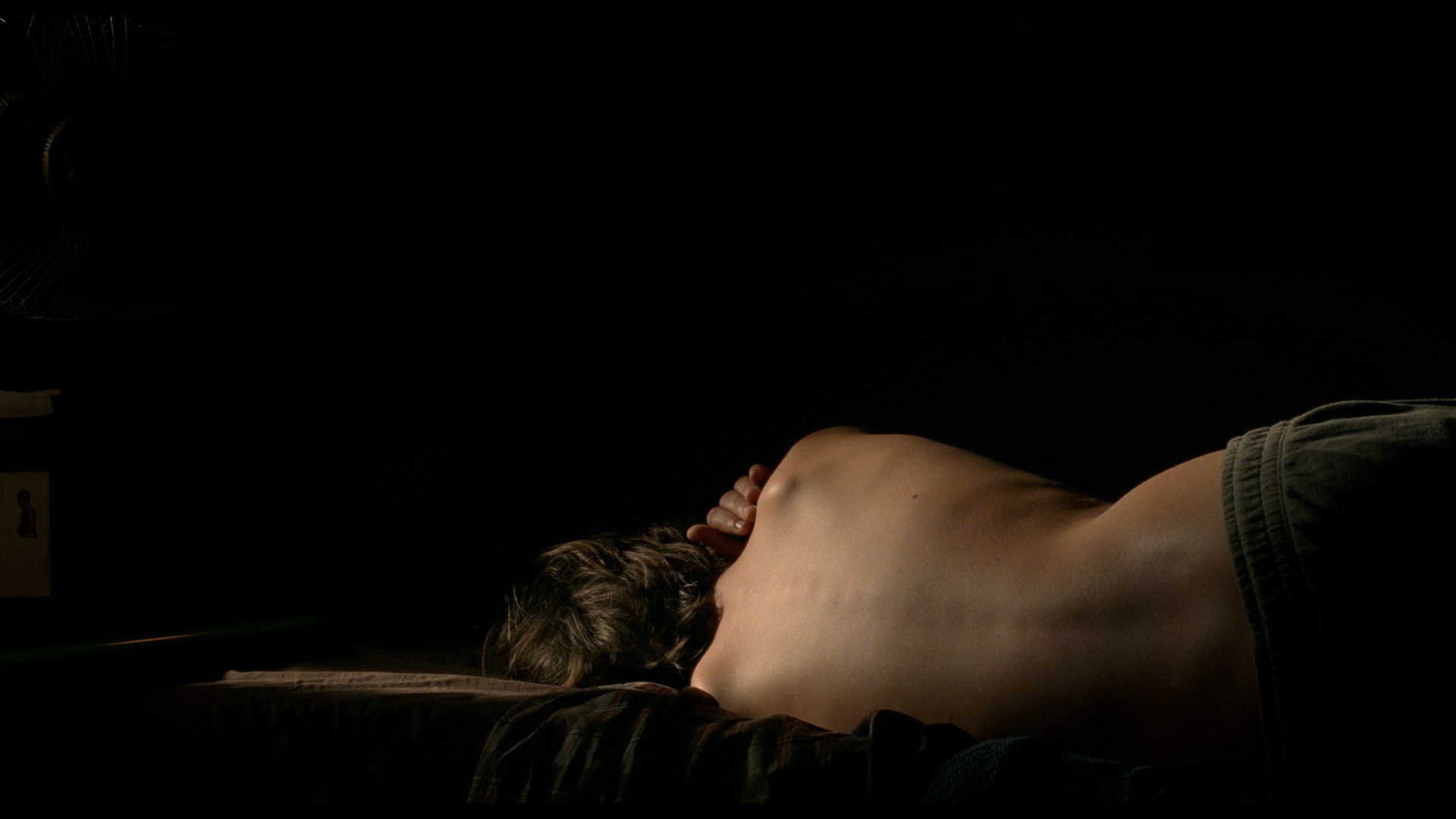

The film it’s my attempt to portrait something like three days in the life of a teenager, but in these days a lot happens to him, so it’s a kind of rite de passage, a theme I’m really interested in, so how this body in motion can tell his own story during this small period of life. The protagonist has the grandfather about to die in the hospital, but he has also his first sexual experience. So a lot happens I was trying to film these very intense days of a teenager and also memories from my own adolescence.

Why did you choose this story, how did you come to it?

I think it’s a combination of my own memories… I like this idea that like a painter is not painting what he is watching but what he rembembers. Memories are very cinematic because we only keep the important images of the past, only the details that really mean something. To me memories are images and as a filmaker writing memories is good because they are not only words, but images that are in my mind. So the film is a combinations of elements and sensations of my own adolescence and experiences of David, the name of the character and the actor is the same, so how my memories as a teenager of fifteen years ago can connect with his own experience to tell a story together.

From the script to the shooting did you make any changes?

Yes, a lot. I like this idea of Robert Bresson that the script exists to be destroyed during the shooting and the shooting exists to be destroyed during the editing. So it’s a permanent layer of destruction and reconstruction during the process. When I write I know that what I’m writing will go through that, I’m not very attached to what I write, I write a very simple line, beginning, middle and end, the basic story arch, but for the rest I continue to write on the set, with the actor, through improvisation, to collect the kid’s stories, to watch things that then I include in the script: so someday we shoot without script or someday we start from zero. I think that this old idea of the scriptwriter alone tiping in his dark room, drinking and smoking, it’s not working anymore, for me. I think that it’s pretencious to think I have the all world in my mind, then the film would be an illustration of my thoughts. I like to do the opposite: go to the shooting with a script that you can burn if you want. And I believe that the actors, or the people I have in front of camera, know their characters much better than me and I think that’s the difference beetween literature and cinema. In literature there are no characters, Flaubert can do whatever he wants with Madame Bovary, he knows every thing about her, he can kill her or marry her, he can do anything just has to write it. While in a film there is a body who knows better than me: if I tell the actor he should drink with his left hand and he tells me “I can’t move my left hand, I have to do with my right hand…” So should I insist with him because I wrote like that? I don’t think so. I always tell the actor: you are the owner of the character. Maybe there are no characters, but presences, bodies, and then I write with the camera, filming these bodies. I can do that because I write my movies, I don’t work with scriptwriter, I don’t buy the script from someone else, and I think than many scriptwriters also should do their own films, because when they have good ideas finally they are disappointed if the director changes things. I don’t have a very classic approach to scriptwriting.

I think it’s a very european point of view, you quoted Bresson and also I read that beetween your references there is Antonioni, it’s an author approach.

But the writing it’s still there, maybe there is not a 90 pages script, but there is writing, you write with the camera, you write with the people, in the editing room. I just don’t see myself alone writing beautiful sentences that in the end have nothing to do with the people I’m filming.

So you are very open to reality, and I felt that especially in the way of filming the city of Lisbon, it’s quite unusual. What kind of relationship there is beetween the character and the space?

Yes I didn’t film the postcard Lisbon. To me is very important that, and that is what I love in cinema and in the first films of Lumiére: while in theatre you have to paint a big wall to reproduce a city, to give the idea of the city, in cinema you have the city not behind, but on the same level of people, so space also tell the story. I like to feel that the building and the spaces that you see on the screen refer to moments in the past of characters, even if you don’t mention that. For example the way you sit on a chair in a bar is completly different from the way you sit on your sofa at home, you have a story with that sofa. The way in wich characters play and interact with space is also telling something of the story. To me it’s important to find places that I like to film, but also include them in the life of characters; I like the interiors to be full of life, with trash and dirty clothes around. Especially in Montanha the places in the city are the secret corners for the kid, the places where he likes to hide. I choose places for the way they are connected to character, not just because they are beautiful to film. In my film the city is breathing, is alive, so it’s not the postcard Lisbon.

I found interesting that this main event of the grandfather’s illness is off screen. We know that the kid is very attached to him and we see the kid visiting the hospital, but we never see the grandfather. Why did you make this choice?

I thought that it would have been stronger to stay with the kid and share his rejection of that problem. The kid refuses to go inside the room in the hospital, this is a very adolescent feeling where you have both happyness and anguish walking side by side in the film. The kid try to escape the reality, he wants to go away and just fall in love with the girl. There is a sort of statement that the kid is doing: I want to stay in the kid’s world, I don’t want to grow up as fast as reality is telling me to grow up and actually I don’t believe that my grandfather will die. So in the film the camera is all the time filming the kid point of view, so it would have been contradictory showing something that he refuses to see. So the grandfather is present as a shadow. And I think it’s stronger like that. I don’t see the film director as god, you know about the fact that camera should show more than what the character knows, I don’t believe in this narrative strategy, because I’m more interested in the things that people I’m filming have to say than in what I have to say. Also in chosing the position of the camera I follow the actor movements, I don’t give directions to actors based on the position of the camera. And also filming adolescence is about this mistery, it’s about how they move, how they hide. So for example in the scene where the two kids kiss for the first time, I go and go away with the camera from them, I think it’s important to keep this distance, to be careful on how far I can go as a director, this is part of my work. I didn’t want to make a film about kids with drugs, naked scene, maybe I’m probably conservative, but the films I like are old films, like Nicholas Ray, I like Rebel without a cause, its a film that was always very present in my mind while I was shooting, especially that kind of James Dean’s anguish, wich is hard to understand. So it’s contradictory, because I wanted to film something new and fresh like adolescence, but with a old style, a classic language, it’s not a iperrealistic film, with hand camera and lot of movements.

Did you have in mind a particular audience for the film, maybe kids?

I’m very selfish and I think only about the film, so first the film has to be important for me. Then obviously I wish the film creates echoes in other people, but I don’t think of that in terms of target. The beautiful thing about cinema is that you’ll never know what happens to a film, if it will touch or not the heart of people and I think it’s pretencious try to anticipate what people will love. In American Hollywood film they think of film first as a product and then as a film, but I always think of it as a film then is the producers and distributors work to sell it as a product. I like this metaphor that the milk that comes from the cow’s tits is basically milk and become a product when you put it in box to sell it, so I am the cow doing the milk.

How is the situation of cinema in Portugal at the moment? The film festival director Barbera said that there are too many low-budget films and that leads to low-quality.

In Portugal all the films are low budget. Two years ago was Portugal anno zero, because there was no produced film at all. The fascist government, write it, that we have now, closed the ministry of culture and for two years we had no public funding for the cinema. In the last year we had a big fight with the government and the filmmakers, we asked: do you want to stop cinema in Portugal, are you crazy?? So slowly it’s starting again, but we have low budget if you compare to other european movies, in Spain, France. So now portoguese cinema is coming back, and considering o the small number of films we produce it’s amazing how in the main festivals there is always a portuguese film. Then you know in Portugal we don’t have a cinema tradition as rich as here in Italy or in France, the story of cinema in Portugal is very simple: it’s Manoel De Oliveira. Then you have fascist cinema until the 60s, they were very bad comedies supported by Salazar; then in the 60s there are two directors, Fernando Lopes and Paulo Rocha, who started to make neo-realistc films, that were something different. So now my generation has the heritage of these cinema made in the streets in the 60s, the history of portuguese cinema for me starts in the 60s. We don’t have this tradition of classic cinema as in France or Italy, so for the government and the élite cinema it’s not important as an art, so films have always been something crazy and dissident, as directors we are used to clash with the government.